It's no accident that not driving is still the hardest way to get around Minneapolis. More than half a century's worth of decisions by local officials have led to a city designed primarily to serve automobile traffic. This has created neighborhood streets that inconvenience and threaten the safety of anyone not traveling in a car. It's a destructive trend that, despite recent victories on bike lanes and parking reform, hasn't yet reversed itself.

Alex Cecchini, an expert who has written smart things for streets.mn, thinks we could be doing more to make not driving easier: "On one hand, biking and transit are easier and less scary than your regular suburban commuter assumes. On the other, it really is way more complicated and shitty than it needs to be."

Biking / transit require more physical activity than driving, interrupting the planned atrophy of my muscles.— Jeff (@j3effcSTP) September 3, 2017

Too Many Cars, Not Enough Buses

Whittier resident Mike Beck says local buses are crowded and don't come frequently enough. On the way home from his son's football game, he says, "the bus was so crowded, I had to stand." And when he attempted to transfer to a second bus, the wait was so long he decided to walk 13 blocks home.

Residents like Sam Jones of Stevens Square place some of the blame on the sheer number of cars clogging city streets. After a long train ride from Chicago, Jones says he was deprived of a bus ride home by "suburban dad traffic" that jammed downtown streets following the conclusion of a teen-oriented pop concert.

He says he waited for an hour in the rain, "even though there are four routes that directly connect my neighborhood to the Hennepin LRT station, three of them high frequency."

Rising CostsSaturday standing on the 5. This is my not-driving horror story. @StarTribune pic.twitter.com/CuLSAlCINx— Wedge LIVE! (@WedgeLIVE) September 9, 2017

Not only is sharing road space with cars a major inconvenience and potentially dangerous, but it can also be costly, as Adam Miller found out when "a car backed into me in the Portland bike lane and I had to walk to [the bike shop] for a new front wheel."

For bike commuter Nicky of Elliot Park, a lack of secure bike parking means their transportation costs are on the rise, in the form of repairs and replacement parts.

They describe having to "lift my bike up off the sidewalk about 3 feet to lock it to the fence every single day. I have to use 2 locks, because my front wheel got stolen from this insecure location a few months ago, so I lock the frame and rear with one u-lock, and the front to the frame with a second u-lock. And, it's not covered, so my components are rusting fast thanks to our increasing rainfall levels."

Cost will soon rise for transit riders as well, with Metro Transit set to increase fares by 25 cents on Oct. 1, with no increase in service. This is due to the GOP-controlled state legislature's refusal to fund transit at an adequate level.

Concerns for Safety and Comfort

In addition to the usual safety concerns a person might have walking, biking or taking transit--including from drivers distracted by cell phones or from streets designed as high-speed thoroughfares--non-drivers also contend with aggressive behavior and outright harassment on their commutes.

"People have shouted slurs at me numerous times walking," says Ryan Johnson of Prospect Park.

"Pretty sure I was about to get assaulted once in Northeast, but the bus arrived at the right time," he said. "Things like that make me prefer to bike so I can GTFO fast, but then obviously, no escaping assholes in trucks. My former roommate had numerous experiences where drivers would road rage and shout slurs because he didn't seem straight enough while biking."

Perhaps more disturbing than street harassment is the mental anguish I have personally experienced reading comments on the nextdoor website from people pretending that a new bike lane has delayed their car trip by 30 minutes.

|

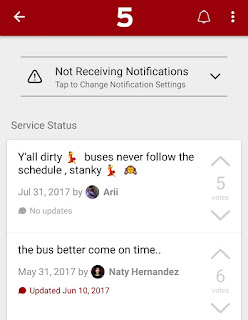

| Rider comments via Transit App show not-driving is harder than it should be |

With all the danger, discomfort and inconvenience they face on their commutes, non-drivers sometimes laugh at the parking concerns like those of a suburban lawyer who'd rather drive to work downtown than take an express bus. He makes this choice even though not driving would cut his parking expenses by $1,500 annually and get him to work in the same amount of time. Most city-dwelling transit riders would be fortunate to have a bus commute anywhere near as speedy as a car trip.

Noted guy in the Wedge, John Edwards, who is writing this blog post right now, asks, "Why exactly should a car get to live downtown rent-free for a year? We seem to understand that real estate has value as a place for people or businesses, but too many people think land stops having value the moment someone wants to park a car on it."

Some residents make arguments that because biking or transit is harder than driving, we should double down on the automobile-centered design of our city. This only perpetuates the problems, says Edwards, guy who has read the comments on the nextdoor website (editor's note: I am John Edwards).

"People say we should forget bike lanes that make it safer for people to commute by bike because it feels like their commute might be slower," Edwards observed. "They point to a lack of adequate transit as the reason we should layer our cities with as much free parking as possible, instead of pushing for policies that make better transit viable. This is largely concern-trolling from comfortable people averse to small changes."

Considering (1) the hazard cars pose to people and the environment; (2) the cost that free parking adds to the price of housing and other things we buy; and (3) the opportunity cost of land we dedicate to parking not serving some other, more productive use; driving remains embarrassingly cheap and easy.

If you believe in the kind of journalism where a reporter isn't afraid to quote himself in his own story, support Wedge LIVE! on Patreon.